Again and Again Theif Anne Bradstreet

Anne Bradstreet was a deeply ambitious poet who was far from surprised by the publication of her get-go book.

There are no extant portraits of Anne Bradstreet (1612-1672), the "first" American poet. Simply on the Spider web, when 1 Googles Bradstreet, a popular nineteenth-century painting pops upwards. An imaginary Bradstreet sits at a desk-bound, wearing a white bonnet and a white apron, looking modest and soulful, exactly as the Victorians thought a Puritan woman should look. This epitome is replicated throughout the Spider web, actualization on the Poetry Foundation and Wikipedia pages for Anne Bradstreet, demonstrating modernity's conception of Bradstreet equally a pious pilgrim, unconcerned with worldly affairs.

It is not that the Victorian creative person was incorrect. Bradstreet was indeed a devout Christian and her piece of work reflects her life-long struggle with her faith. Merely she was far from being the humble bonnet-wearer that the Victorians wanted her to exist. Bradstreet was securely aggressive. She used the give-and-take "fame" 13 times in her starting time 3 poems, reflecting her business almost her stature as a poet and her anxiety that as a woman she would non be allowed to take her place in the pantheon of smashing English poets. She wrote more than seven,000 lines of poetry, addressing topics that were considered far too complex for a mere woman, including the history of the earth, the current state of the sciences, the political relationship between the old and new worlds, and the many religious conundrums of Puritanism.

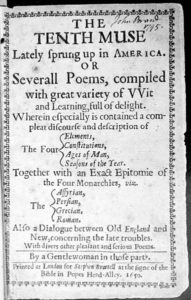

How, and so, did this Victorian prototype of Bradstreet come to dominate the airwaves? Maybe the answer lies in the propaganda entrada that Bradstreet and her family unit launched afterwards her book, The Tenth Muse, was published in England in 1650. According to Bradstreet, she was so balky to fame that she did not desire her poetry published. In her poem, "The Author to her Book," she declares that the manuscript was "stol'due north" from her. The thief was her blood brother-in-law, John Woodbridge, a "friend more loving than true." When Woodbridge found a publisher for Bradstreet'due south work in England, he did this of his own accord, she implies, leading readers to believe that her book was published behind her back, without her knowledge. And and then began the story that modernistic readers nonetheless believe today. Bradstreet'southward words are reinforced past the prefatory fabric Woodbridge included in The Tenth Muse. He claims that Bradstreet's poetry came 2nd to her womanly duties. She went without sleep to write, he declares, and never scrimped on her chores. Starting time and foremost, she was a wife and female parent. The last matter she wanted was fame.

Unfortunately, readers take taken these claims at face value, overlooking Bradstreet's sophistication as a poet, her skills as a disguise artist, and her youthful appetite. But if one reads Bradstreet's poesy with close attention, one finds work that is replete with double meanings and ironies, self-deprecation and even self-condemnation—strategies she had learned in a culture that disparaged women for trespassing in realms that were considered male territory. This is not to say that Bradstreet's cocky-deprecation was insincere. It would take been difficult for Bradstreet, or, for that matter, any seventeenth-century woman, to free herself from the prejudices of the fourth dimension. The experts taught that women were weak, vulnerable, and foolish—criticisms that were internalized by Bradstreet, who had witnessed showtime-hand what happened to outspoken women. In 1638, just twelve years before the publication of The Tenth Muse, Bradstreet'due south acquaintance Anne Hutchinson was banished from Massachusetts Bay for holding meetings in which she criticized the colony's ministers and challenged male government.

As a result, Bradstreet had learned to couch her ambitions in terms that were acceptable to her time. In one early poem, the poet/narrator tries to scale Mount Olympus to beg aid from the classical muses, but is driven off the mountain because she is a adult female. Still, instead of accepting her fate equally a lesser poet, she declares that she is not cast downwardly, as she will have a "amend guide," the Christian God, a muse infinitely superior to the pagan gods of classical artifact. In the prologue to her long verse form The Quarternions, Bradstreet writes that male poets deserve laurel wreaths for their piece of work whereas she, a woman poet, volition be content with a simple wreath of thyme. But of course "thyme" is a homonym for "time," and so the conscientious reader can run into that Bradstreet'due south credible self-deprecation is actually a disguised proclamation of her ambition. Men's achievements, she declares, may win them worldly fame, but she, as a woman poet, aspires to more than than this—everlasting acclaim, eternality itself.

This dependence on indirect assertions and strategic twists makes Bradstreet'due south work unusually circuitous—ane of the reasons she is even so read today. Just her sophistication as a poet did not come easily. From the first, she was serious about her craft, studying the poets of previous generations to improve her skills. Her early poems are full of learned allusions and witty figures of spoken communication. Over time, nevertheless, she inverse her style to adjust her deepening delivery to New Globe Puritanism, vowing to use "plain speech." Thus, although she lamented that The Tenth Muse was made of homespun material rather than expensive silk ("The Author to her Book"), she was intent on developing a New England Puritan aesthetic that she believed superior to Erstwhile World poetics. Not for her the elegance of Elizabethan versifiers. No more than emulation of the past. Instead she would take her place as a New Globe adult female poet, a pious Puritan who would utilize elementary language to express her humble devotion to God. Again, although these pronouncements are intrinsically self-deprecatory, they are also statements of Christian ascendancy. For who goes to heaven first? The poor, the meek, the humble. Accordingly, Bradstreet's declarations of humility were also declarations of superiority, at least in the Christian sense. Bradstreet had been taught to believe that when the end times came, she and other humble pilgrims would be raised above those who seemed more powerful during their time on world. New England herself would exist ascendant over Old England, considering of New England'southward superior piety.

Only despite Bradstreet's assertions of Christian ascendancy, information technology does not necessarily follow that she wanted her manuscript published, or that she had any advance knowledge of John Woodbridge's publication scheme. It is in her poetry, which has always offered rewards to the careful reader, that she reveals that she was fully aware of Woodbridge's try. The inkling lies in one of her least-read poems, "David's Lamentation for Saul and Jonathan." At start glance, this poem appears to be one of Bradstreet'due south least interesting works. A simple reprisal of 2 Samuel 1, the biblical passage where the future Rex David mourns the death of his predecessor, King Saul, and his son Jonathan, Bradstreet seems to offering the reader no new insights into this familiar biblical story. The but distinctive aspect of the poem is that she uses the language of her time; for instance, replacing "daughters of Israel" with "State of israel's dames." Only other than Bradstreet's deployment of seventeenth-century vernacular, the poem seems the most opaque and the least promising of all of her works. In fact, it seems downright dull, until i considers when it was written. And when it was published.

Equally other scholars have pointed out, it seems articulate that Bradstreet wrote "David's Lamentation" later hearing that Charles, the English language king, had been executed past English Puritans. With this in heed, the poem instantly becomes far more than a simple translation of a biblical text. It becomes political poetry, mourning the execution. Withal, Bradstreet disguised her betoken of view, because to offer a direct critique of the English language puritans was unsafe. She did non want them to direct their wrath toward their New World counterparts. Furthermore, the timing of the poem indicates that Bradstreet, or at to the lowest degree someone from the New Earth, sent the poem overseas subsequently John Woodbridge, the one who had purportedly "stol'n" her manuscript, had sailed to England in 1648, a year before the king's execution in 1649. Indeed, Woodbridge had been sent over to help Cromwell negotiate with Charles in order to avoid the violent death of the king. Why does this matter? "David'due south Lamentation" is included in The Tenth Muse, which means that Bradstreet, or ane of her family members, must have fabricated sure that Woodbridge had the poem and so that information technology could appear in her book.

Although it is possible that someone other than Bradstreet sent Woodbridge "David's Lamentation," it is highly unlikely that Bradstreet would have been uninvolved. Vellum was expensive. Information technology was difficult to make multiple copies of poems. Time was of the essence if "David'southward Lamentation" was to exist included in The Tenth Muse. A messenger, a reputable helm and a ship all had to be found. Bradstreet's cooperation would take to exist secured if she and her family wanted "David's Lamentation" in the manuscript.

The evidence of Bradstreet's agile involvement in the publication of The Tenth Muse clears up a centuries-old misconception, revealing her to be a far more complicated figure than the popular Victorian image of her suggests. Yes, she was a devoted Puritan. Simply she was too ambitious, not precisely in the modern sense, every bit she was not interested in promoting her work to earn glory, just equally both a Puritan and a New English writer, she was convinced that her poetry could help spread what she believed was a truer version of Christianity to the English-speaking globe.

Motivated as she was past her organized religion and her commitment to the Puritan mission, one might think that this revelation almost Bradstreet'south active function in publishing The 10th Muse would be entirely uncontroversial; Bradstreet was non a seventeenth-century firebrand, interested in starting a feminist revolution. And yet, the idea that Bradstreet participated in the publication of her volume even so meets with angry resistance from those who would like to keep Bradstreet in her "place" as a submissive married woman and mother. When I amended Bradstreet'southward Wikipedia page to include the evidence that Bradstreet was aware of the publication of The Tenth Muse, 1 angry "editor" disputed this point, stating, "Bradstreet was not responsible for her writing condign public. Bradstreet's brother-in-law, John Woodbridge, sent her piece of work off to be published. Bradstreet was a righteous woman and her verse was non meant to bring attention to herself."

Conspicuously, the idea of an assertive/agentic Bradstreet has hit a nerve amongst readers who would similar to view Puritan women as subordinated private figures, even though these roles are largely a Victorian invention. In the seventeenth century, Puritans did not separate their religious obligations from their civic duties. The Victorian separation between public and individual spheres did not yet exist. Instead, information technology was considered a theological and public obligation to heighten children to be good Christians, and to adhere to one's faith. The publication of a book of poetry that espoused Bradstreet's commitment to Puritanism was certainly an unconventional act, only it could still exist perceived as a fulfillment of Bradstreet's roles as a good wife and mother. Certainly, this was the stance adopted by Woodbridge and the other writers of the prefatory material of The Tenth Muse. As for Bradstreet herself, she was undoubtedly aware that she would face up criticism for writing poetry, and even so she did non permit this stop her—an important betoken that is missed by those who cling to the Victorian image of Bradstreet. Far from shrinking from the public middle, Bradstreet took the courageous step of publishing her ideas, and and then deserves to be remembered not only as one of the bravest pilgrims in American history, but in the Christian tradition.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.three (Summer, 2016).

Charlotte Gordon's latest volume, the dual biography Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley (2015), won the National Book Critics award. She has too published a biography of Anne Bradstreet, Mistress Bradstreet: The Untold Story of America'due south First Poet (2005).

Source: http://commonplace.online/article/humble-assertions-the-true-story-of-anne-bradstreets-publication-of-the-tenth-muse/

0 Response to "Again and Again Theif Anne Bradstreet"

Post a Comment